In recent years, return on invested capital (ROIC) has garnered renewed attention as capital markets demand management that emphasizes capital efficiency. However, ROIC is a double-edged sword that can be counterproductive if misused, particularly for Japanese companies with a strong frontline presence that have become increasingly siloed (with isolated organizations unable to share information). Although ROIC was originally adopted as an indicator to improve business performance and stock price, business units tend to be superficially obedient, leading only to increased management costs and "more labor, less profit.”

Aimed at corporate planning, finance, and accounting professionals who are in charge of ROIC management, this Insight looks at the seven pitfalls hindering improvements in effective ROIC management, and prescribes potential solutions to elude such pitfalls.

The seven pitfalls hindering improvements in effective ROIC management, and possible solutions

Why consider ROIC now?

In recent years, ROIC has garnered renewed attention as capital markets demand management that emphasizes capital efficiency. ROIC, an indicator that evaluates the "earning power" of a company or business, measures how efficiently capital raised through business activities is invested to generate profits.

Firstly, there are only four measures to increase corporate value.

- Increase profits without additional capital investment

- Capitalize on businesses that generate profits in line with the cost of additional capital invested

- Withdraw investments from businesses that cannot generate profitability in excess of their cost of capital

- Achieve lower cost of capital

In view of these points, ROIC-based management, which facilitates the side-by-side comparison of yields on invested capital for each business category, is increasing among Japanese companies.

Points to note when utilizing ROIC

However, it should be noted that, especially for Japanese companies with a strong frontline presence that have become increasingly siloed, ROIC is a double-edged sword that can cause further siloing and dumbing down of business units.

For example, since ROIC is “management of rates,” it may lead to austerity measures in business units and hinder business scale growth. On the other hand, despite the lack of investment in the growth of business units, headquarters leaves inefficiencies unaddressed, further weakening its control. Delays in digital transformation are another example. Additionally, corporate transformation is accompanied by major mergers and acquisitions, but single business units struggle to achieve a reasonable ROIC, making it easy for business units to shift responsibility onto one another.

The seven pitfalls hindering improvements in effective ROIC management

Thus, there are many Japanese companies that have introduced ROIC management, but are struggling with its subsequent operation. Although ROIC was originally adopted as an indicator to improve business performance and stock price, business units tend to be superficially obedient, leading only to increased management costs and "more labor, less profit.”

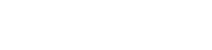

Specifically, there are seven "pitfalls" (Figure 1) that undermine corporate value in the course of organizational management, which are as follows:

Figure 1. Seven "pitfalls" hindering improvements in effective ROIC management (the silo trap that undermines Japanese companies)

Figure 1. Seven "pitfalls" hindering improvements in effective ROIC management (the silo trap that undermines Japanese companies)

1. Between headquarters and business units:

Headquarters is responsible for the founding of specific business units, and tends to be reluctant to sell or withdraw from these respective businesses. This reluctance is compounded by the concern that "withdrawing from a particular business will have a negative impact on other businesses because it will damage common business foundations." According to ABeam Consulting’s Evolving ROIC Management Survey (hereafter “our survey”), companies with low price-to-book ratios (P/B ratio below 1.3) actually tend to be more reluctant to exit businesses than those with high P/B ratios (above 1.3) (for the latter, the ratio of companies that had exited businesses was 28.3%, compared to 11.3% for the former).

In addition, despite lack of investment in the growth of business units, headquarters leaves inefficiencies unaddressed. Employees are not convinced in cases where only the business units are required to meet ROIC targets, leading only to increased management costs.

2. Between business units:

Japanese companies tend to have strong business units that are so siloed that the customer perspective is diluted. In other words, in many cases, business units that should be working hand-in-hand from the customer's perspective end up competing for customers, imposing costs on each other, and even shunning investment in growth, thereby missing opportunities to optimize customer value. In fact, according to our survey, "companies with room for improvement" (companies with P/B ratios of less than 1.3 and no experience of exiting a business) tend to have narrowed down their KPIs in line with their business characteristics when compared to "blue-chip companies" (companies with P/B ratios of 1.3 or higher and experience of exiting a business) (for the latter, the ratio of companies that narrowed down their KPIs in line with their business characteristics was 56.5%, compared to only 16.4% for the former).

Furthermore, not only does the cost of capital concept not permeate the workplace, it does not seem to interest business unit managers. Even though people understand, in theory, that they should pursue yield on capital invested in a business, it is not easy to shake the profit-and-loss thinking that has been ingrained in them for many years.

3. Between management and infrastructure:

Data is held in a rigid manner, making it difficult to flexibly reinforce businesses and organizations with M&As and other investments. There are still many Japanese companies whose code system differs from unit to unit. Many companies are reluctant to build a system that allows them to track ROIC by business category or on a consolidated basis because of the high investment required for data infrastructure. However, if ROIC management is to be considered essential for diverse investment, this is not a sufficient reason.

According to our survey, when comparing "companies with room for improvement" (companies with P/B ratios of less than 1.3 and no experience of exiting a business) to "blue-chip companies" (companies with P/B ratios of 1.3 or higher and experience of exiting a business), the tendency to invest sparingly into data infrastructure is evident (for the latter, the ratio of companies that utilize system management rather than Excel was 33.3%, compared to 9.1% for the former).

4. Between business units and subsidiaries:

Subsidiaries that handle multiple businesses tend to avoid getting caught in dilemmas between business units and often pursue individual company optimization. As a result, consolidated groups have common inventory holdings in subsidiaries which could increase working capital, but because resources are held at subsidiaries, business units may be forced to outsource even when subsidiary capacity is available.

5. Between ESG and business units:

Business units oppose ESG due to the cost burden, and therefore corporate-wide ESG activities tend to lose their centripetal force and become ineffectual.

6. Between technical and administrative C-level executives:

In many large companies, as C-level executives become more specialized, there is insufficient dialogue between technical CTOs and CDOs and administrative CEOs and CFOs, all of whom make management decisions together, in terms of what technology is useful for and what the implications are for management. Subsequently, investments in R&D, DX, and other growth investments tend to be unnecessarily curbed.

In fact, our survey suggests that "companies with room for improvement" are less willing to extract business contribution from their digital investments than "blue-chip companies” (for the latter, the ratio of companies that evaluate the ROI of their digital investments was 52.2%, compared to 14.6% for the former).

7. Between investors and managers:

From the investor's perspective, the return commensurate with the business risk tends to be unclear. In many cases, even with growth investments, managers are unable to explain when and how much an investment will provide returns, and what the risks are. According to some investors, the "value creation story" in integrated reports is too abstract and insufficient.

On the other hand, with KPIs in place and employee buy-in often neglected, managers with a long-term perspective tend to find themselves in a dilemma. In such cases, even if individual KPIs are enhanced, the traps of "partial optimization" and "general agreement, specific disagreement" are common, and company-wide KPIs (ROIC) rarely increase.

Prescribed solutions to elude pitfalls hindering improvements in effective ROIC management

There are, of course, solutions to elude the seven pitfalls hindering improvements in effective ROIC management.

1. Between headquarters and business units:

In order to invigorate the discussion of selling or exiting a business, it is effective to manage business portfolios as a trinity together with technology (or organizational capabilities) and human resources portfolios. This encourages objective discussions by visualizing which businesses should focus on investment and, conversely, which businesses require bold structural reforms, and whether eliminating those businesses would result in an outflow of valuable technology and human resources.

In addition, before requesting business units to improve ROIC while leaving inefficiencies unaddressed, headquarters should start by cutting their own costs (HQ cost structure reform).

2. Between business units:

In order to extract the full potential of each business unit, KPIs should be constructed from the customer value point of view. It is necessary to make choices carefully based on the premise that "a wrong outcome indicator does not produce results, and may have the opposite effect." Thinking along the KBF (Key Buying Factor) and value chain axes, one must identify what factors are important to customers and whether those factors are stagnant, pinpoint what is causing the blockage (that is the “key”), and then set those identified factors as KPIs (i.e. "what" to aim for).

It is also important to specify "who" carries the weight of the identified KPIs. It is not easy to instill balance sheet thinking, particularly in employees who are steeped in profit-and-loss thinking, so consideration must be given to the “who.” For example, regarding the overhead cost allocation problem, which is common when calculating consolidated business ROIC:

- Allocate sales, general, and administrative expenses and fixed assets, which are often shared by multiple business units, to large business units (large segments) instead of unnecessarily allocating them to small business units (small segments) ("Balance sheet by business category" is broken down by large segment units with similar business models)

- Ensure, however, that small segment leaders are jointly responsible for the ROIC of the large segment

- Set ROIC targets in two tiers: a "hurdle rate," which is based on direct costs plus a margin that should be recovered, and an "expected value," which also requires the recovery of overhead costs

Hopefully, these approaches to expense items, hierarchies, and targets can offer some solutions.

Additionally, providing prospective leaders with tasks that include balance sheet responsibilities for projects and subsidiaries, much like with general trading companies, and letting them take ownership of the tasks, could prove effective when encouraging balance sheet thinking to take root.

3. Between management and infrastructure:

To change the rigid way data is held, the data infrastructure for consolidated business management needs to be restructured, with the key being how to integrate data that is scattered across the company and difficult to totally replace. An effective way to achieve this is to establish a data integration tier (second tier) that consolidates scattered data into a form that can be utilized across the board (third tier) on the premise that existing IT assets (first tier) can be utilized through a three-tier architecture.

With the seven pitfalls in ROIC management operations, there is a high risk of rework if large-scale ERP modifications are made suddenly, and therefore, the process should start with spreadsheet compilation, followed by RPA, followed by large-scale modifications in conjunction with periodic ERP updates, and so on, in a sequential manner.

4. Between business units and subsidiaries:

To prevent subsidiaries from favoring individual optimization, it is important to reallocate the original functions of the subsidiaries, and to revise group organization by, for example, organizing flow distribution. This has significant IR benefits in that it makes the structure of business consolidation easier to understand.

5. Between ESG and business units:

In order to gain approval from the business units regarding the ESG cost burden, it is effective to lower the hurdle rate in return for a reduction in the cost of capital. However, the trouble with this is that fairness among units cannot be maintained unless it can be rationally explained that contributions to units are equivalent to "the effect of capital cost reduction by unit." In this regard, it is good to promote the visualization of ESG value in a data-driven manner.

6. Between technical and administrative C-level executives:

To create a common language base among C-level executives regarding the technology agenda, a technology resource inventory (a strategic technology management approach) is effective. This allows the assessment of priorities and the necessary scale of technology investment from a customer value perspective.

Although some object to this by arguing that basic research or company-wide infrastructure have infinitely wide-ranging applications and cannot be linked to business contributions, every technology investment should have a main target (application) in mind, and it is quite possible to demonstrate this as a contribution to the business (customer value). This can be structured by drawing a technology tree from the customer value point of view.

7. Between investors and managers:

To clarify returns commensurate with the business risk from the investor's perspective, it is necessary to show what type and amount of investment is needed, why, when it is likely to be recovered, and the path to cash generation. Generally, we should factor into this explanation how different types of businesses in the same corporate group earn different amounts of money. For example, business types can be classified from a profit-and-loss perspective (advantage matrix: potential economies of scale and differentiating factors) and a balance sheet perspective (investment and returns cycle duration).

To avoid falling into the trap of partial optimization with KPIs, the prioritization of various measures should be determined by returning to the corporate philosophy (the company's raison d'etre and purpose).

These are some potential prescriptions to elude the pitfalls hindering improvements in effective ROIC management. It is worth noting that these are not simple solutions and the hurdles for implementation are not low. This emphasizes the importance of approaching it through an appropriate system.

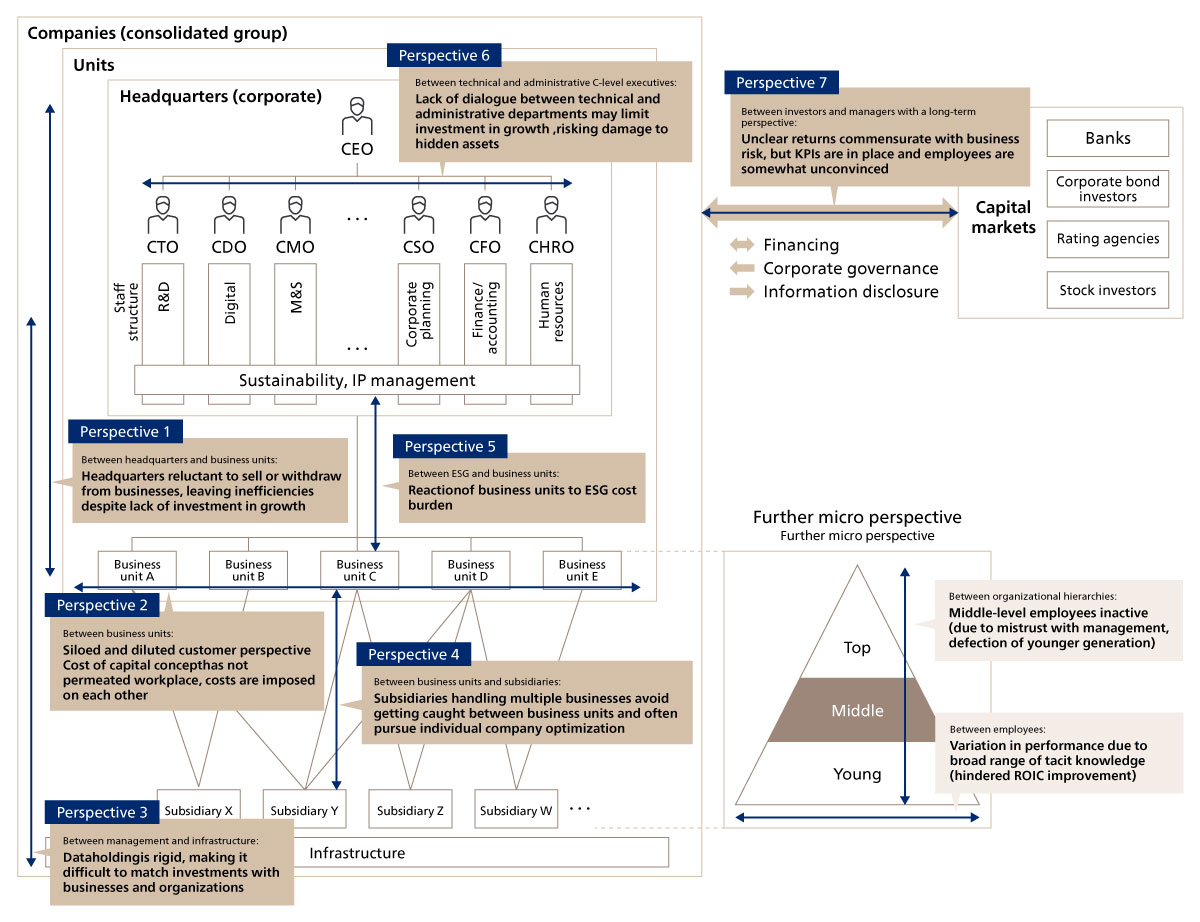

While ROIC management is generally thought of as the CFO's agenda, it is also closely related to other C-level executives and evolves as a hub that connects the entire company, as shown in Figure 2. Perhaps this could be utilized as one of the guidelines to eliminate the silos of Japanese companies.

Figure 2. ROIC management, an evolving hub that connects CFOs with other C-level executives

Figure 2. ROIC management, an evolving hub that connects CFOs with other C-level executives

ABeam Consulting will continue to support the realization of rapid and reliable ROIC management by providing consulting services in line with the different objectives and stages of individual companies.

Click here for inquiries and consultations