Pro bono Project (JANIC)

Examples of Pro Bono Activities

~Utilizing Company's Core Business Skills~

Japan NGO Center for International Cooperation (JANIC)

1. Introduction

The term “Pro Bono” (from pro bono publico, Latin for "for the public good") refers to the participation of company employees and other working adults in social contribution activities and initiatives aimed at solving social issues by utilizing the expertise and skills they have developed in their career. ABeam consulting has been involved in pro bono activities for years as a part of our CSR activities outside operating hours, but in order to make further impact, we have started engaging in socially significant projects on a pro bono basis, utilizing expertise and skills as a consulting firm. One such project is to support the Japan NGO Center for International Cooperation (JANIC), a network NGO.

*For more detailed information on the research portion of this project, please refer to the white paper that has been published.

2. Project Objectives, Background and Approach

Our client, JANIC, is one of Japan's leading network NGOs, founded in 1987. A network NGO is an organization that functions as a support center for NGOs by providing capacity-building measures for its member organizations (Japanese NGOs), policy recommendations to the government, and educational campaigns for civil society.

In the the field of international cooperation in Japan, which JANIC has supported, there has been a lack of visualization of the current status of social issues that NPOs and NGOs have been working to solve, and the results and value of their efforts have not been properly communicated to the public. In recent years, the environment surrounding the resolution of social issues in Japan has been undergoing a major transition, with an increasing number of companies engaging in practices such as corporate sustainability and CSV management that aim to achieve a sustainable world through their business activities, and an increasing number of young people, known as "Social Good Natives," who are motivated to tackle social issues.

In response to this emerging trend in which not only NPOs/NGOs but also corporations and individuals are turning their attention to social issues and proactively working to solve them, there is a need to redefine the role of NGOs. With this background in mind, this project was implemented with the following three objectives.

- Visualize Japan's efforts in the field of international cooperation to date and their respective impacts

- Formulate a vision for the future of Japan's international cooperation and the role of NGOs/NPOs in it

- Establish a roadmap to realize the hypothesized future vision

To achieve these objectives, we took the following three approaches.

① Landscape Analysis: Gather financial data on the NGOs from scratch to visualize the market environment.

→ Formulate hypotheses regarding the future of international cooperation area and strategies that JANIC should take.

② In-depth Analysis: Interview key NGO industry experts (26 experts) to gather firsthand insights,

→ Validate and brush up the hypotheses established.

③ Future Vision and Business Strategy Formulation: Develop a feasible strategy through discussions and workshops with members in various positions (from management to the frontlines) who belongs and support NGOs.

3. Current State of International Cooperation

First, we attempted to collect market data on NGO to get a bird's eye view of the market environment. However, financial data for NGOs were not collected, and there was no comprehensive market data available. Therefore, we collected financial data from 120 major NGOs across a10 year span through financial reports published on the Internet and created a financial database with more than 1,200 rows of data. In addition to this database, we conducted a landscape analysis of the international cooperation, using public information from government agencies and public data from thinktanks.

From the research result, we found that the number of new NGO founded has declined significantly from a peak of 172 in the 1990s to 69 in the 2000s and 4 in the 2010s. The overall number of NPOs, including those not supporting international cooperation, remained largely unchanged at just over 9,000 organizations in each of the last 10 years. Since the number of new NGOs has been declining significantly, the number of organizations has not increased beyond the existing organizations.

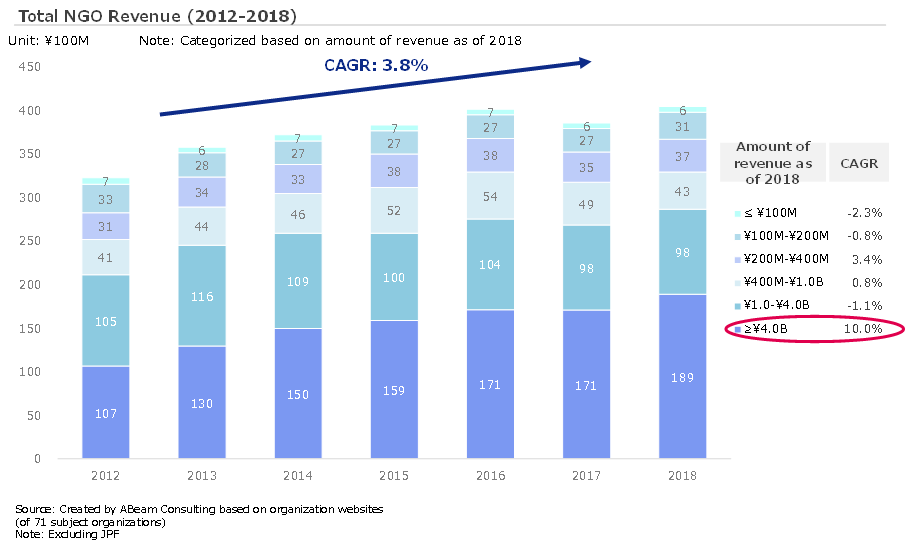

However, looking at the overall market size of the NGOs based on the financial data collected, we found that the overall market is gradually expanding, as large organizations with revenues of more than 4 billion yen are increasing their revenue consecutively each year.

On the other hand, we found that small and medium-sized organizations with revenues of less than 400 million yen showed uneven growth, and there were a certain number of small organizations, especially those with revenues of around 100 million yen, that showed low/stagnant growth rates.

Next, we surveyed the amount of financial assistance provided to NGOs by each stakeholder to understand the state of the international cooperation for NGOs.

The amount of financial assistance provided to NGOs by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (ODA) has been stagnant in recent years, with a growth rate lower than that of other countries.

On the other hand, individual donation shows that the number of donors (2009: 37.66 million → 2016: 45.71 million) and also the amount of donations per person had also been steadily increasing (2009: 14,485 yen → 2016: 16,968 yen). In recent years, various types of donations have emerged, such as the "dormant deposit" system, in which deposits in an account that has remained inactive for 10 years can be used to subsidize NPO activities, the "bequest donation" system, and the "redemption donation" system, and thus individual donations are expected to increase even more in the future.

The number of foundations that provide grants to NGOs has also plummeted since the burst of the bubble, and although there has been a slight increase in recent years, it has yet to recover significantly. In addition, corporate donations have been slowly increasing with the occurrence of major natural disasters, but the growth rate for the number of corporate donors has remained stagnant.

However, the amount of social impact investments (investments made primarily by the private sector with the intention of generating social and environmental impact alongside financial gains) is increasing rapidly (2016: 33.7 billion yen → 2019: 448 billion yen), and a certain number of companies are making investments tied to SDGs.

In addition, ESG investment (investment that emphasizes and selects companies that considers the environment, society, ) has been expanding both globally and within Japan since 2014, and research has shown that companies with higher ESG ratings tend to have higher corporate value, so we can expect further growth in this area in the future.

Furthermore, in recent years, social businesses, like NGOs, have matured as players in solving social issues in the field of international cooperation, pursuing social benefits while achieving business sustainability. The overall sales and organizational scale of social business operations have been steadily expanding and are expected to grow even more in the future.

Examples of social businesses in Japan include Motherhouse, which produces goods and apparel in developing Asian countries and sells them in developed countries, and Borderless Japan, which engages in a wide range of activities such as stabilizing the incomes of farmers in developing countries and expanding employment opportunities for the poor. Borderless Japan's Entrepreneurship Support Program is growing rapidly due to the ecosystem in which surplus funds generated by the program are used to launch new businesses.

Similar to social businesses, local start-ups are also attracting attention as new actors in solving social issues.

In recent years, there has been a significant increase in the influx of capital to startups across Southeast Asia and Africa. Although their target demographics currently differ, as NGOs target low-income groups while local start-ups target upper to middle-income groups, local startups are gradually expanding their audience to include those with lower incomes. As the global volume zone is shifting from low to middle-income groups, it is expected that the target demographics for local startups and NGOs will begin to overlap further in the future.

4. The Future of the International Cooperation

Taking into account the current situation described above, we interviewed 26 experts of international cooperation. Based on feedback from a wide range of participants, ranging from those in their 20s who serve on the board of directors of small organizations that have just been established, to those who have been active on the front lines of the industry for nearly 50 years since before the term NGO became popular, we developed a vision for the future of the field of international cooperation and the NGO sector.

From the results of the industry analysis and interviews, we concluded that the international cooperation sector should aim to create a diverse ecosystem in which multiple mega-NGOs and small to medium-sized organizations can coexist while growing in scale and stability, and that the NGO sector as a whole should aim to expand its financial scale in order to achieve this goal.

Previously, there was a tendency in some segment of the NGO industry to value "small is beautiful," and to emphasize quality and grassroots support over financial growth. However, the results of this survey suggest that in order to generate steady positive impact in developing countries, NGOs need to give more importance to financial growth, while continuously treasuring the value for "small is beautiful."

In addition, Japanese NGOs have traditionally operated on the basis of "activism," namely, the desire to change the social structure that gives rise to social issues, but in the current era of remarkable economic growth and increasingly sophisticated problem-solving methods, the “business-like" nature of support projects from NGOs to local beneficiaries is becoming more pronounced. Many industry experts saw this change as a challenge, arguing that NGOs are too focused on business activities and are not fulfilling their original role of working with various people and transforming society as a movement.

Therefore, the future will require a system for solving social issues (“collective impact”) that involves not only the NGO sector but also private companies, citizens, and other diverse actors in order to achieve a balance between business and activism. One could say that we in business, by helping to address social issues, pool our sector’s particular strengths with those of other sectors, heightening the effectiveness of each other’s efforts.

5. JANIC’s business strategy

To realize the above future vision, we formulated a plan for what JANIC should work on and a strategy.

Specifically, we redefined the target audience. Previously, JANIC had focused on providing support to NGOs originating in Japan and Japanese branches of overseas NGOs, but we expanded this to include social ventures, private companies, and influential individuals in order to create a system for solving social issues (“collective impact”) that involves a diverse range of actors. JANIC will build relationships with the newly targeted social ventures and private companies by proposing methods for solving social issues and providing them with knowledge of the latest trends in the social space.

In addition, for NGOs (JANIC’s original target audience), we focused on the fact that support needs differ depending on the size and type of organization and decided to subdivide them in a way that provides the most appropriate services to each segment.

Based on the future vision for the international cooperation sector as a whole and the target audience defined above, we concluded that the business model that JANIC should pursue is a "platform model" that links support services, networks, and human resources among social issue-solving entities.

However, instead of jumping straight into the platform business, it is necessary for JANIC to gradually strengthen the foundation of its network and execution capabilities, beginning with a “coordinator model” that introduces suitable individuals and organizations to NGOs with issues, followed by a “training model” that implements and introduces training programs to improve NGO skills, and a “think tank model” that identifies the latest trends in the social sector and conducts research and analysis.

The coordinator division will further expand the existing network while promoting the attractiveness of JANIC within the industry, which will lead to the acquisition of new members. The training division will raise the level of JANIC's capabilities while steadily improving the skills of organizations that undergo training, and the receipt of training participation fees will ensure the profitability of JANIC so that it can continue to demonstrate its value.

We also developed a roadmap for realizing these projects, which includes specific proposals for both short and long-term measures, as well as the changes in capabilities that will be required for each project.

We believe that these steps will lead to the development of a platform where various actors can interact with and help each other, and eventually achieve a state where active and voluntary interactions among actors are encouraged, regardless of whether or not JANIC is involved.

6. Conclusion

This support project for JANIC began with the visualization of a largely unexplored market situation in the NGO sector. We then surveyed and organized information that is crucial for JANIC to further demonstrate its value as a network NGO and develop operating strategies to promote solving social issues in the field of international cooperation.

While this project required the rapid acquisition of industry expertise in the social field, which is rarely handled in the consulting industry, there were many areas in which we were able to fully utilize the consulting skills that we have accumulated to provide value to the client. Through this project, we have realized once again the importance of applying the skills acquired in the business world to solving social issues.

As a management consulting firm originating from Japan and Asia, ABeam Consulting will continue to engage in valuable pro bono activities by leveraging its accumulated expertise in problem solving and its relationships with various stakeholders, including NGOs, corporations, and governments.

PARTNER'S VOICE

This survey has once again revealed the importance of cooperation with other sectors in co-creating a global symbiotic society, which JANIC sees as an "ecosystem" and will play a role as a catalyst in nurturing. We would also like to express our gratitude to all the employees who cooperated with us on this project on a pro bono basis, and we look forward to continuing to work with them as we build the ecosystem.

Chairman, Japan NGO Center for International Cooperation

President, NPO Kamonohashi Project

Board Member, Japan Association of New Public